After successfully migrating 44 wireless devices to proper VLANs, I felt pretty good about myself.

- Wireless segmentation: ✅

- Zone-based firewalls: ✅

Time to tackle the infrastructure, right? Well, Proxmox had other plans.

The Plan

I have two Proxmox hosts running my homelab:

- pmxdell: A Dell laptop with one VM (Azure DevOps agent)

- pxhp: An HP ProLiant with 17 VMs (three Kubernetes clusters)

The goal was simple:

- Move Proxmox management interfaces to VLAN 60 (Services)

- Move VMs to VLAN 50 (Lab)

- Celebrate victory

The execution? Well, let’s just say I learned some things about Linux bridge VLANs that the documentation doesn’t emphasize enough.

Day 1: pmxdell and False Confidence

I started with pmxdell because it was the simpler host—just one VM to worry about. I configured a VLAN-aware bridge, added the management IP on VLAN 60, and restarted networking.

Everything worked. pmxdell came back up on 192.168.60.11. SSH worked. The Proxmox web interface was accessible. I was a networking wizard.

Then I tried to migrate the VM to VLAN 50.

qm set 30000 --net0 virtio,bridge=vmbr0,tag=50

qm start 30000The VM started. It got… no IP address. DHCP requests disappeared into the void. The VM had no network connectivity whatsoever.

The Investigation

My first thought: firewall issue. But the firewall rules were correct—LAB zone could access WAN for DHCP.

Second thought: DHCP server problem. But other devices on VLAN 50 worked fine.

Third thought: Maybe I need to restart the VM differently? I stopped it, started it, rebooted it, sacrificed it to the networking gods. Nothing.

Then I ran bridge vlan show:

port vlan-id

enp0s31f6 1 PVID Egress Untagged

50

60

vmbr0 1 PVID Egress Untagged

60See the problem? VLAN 50 is on the physical interface (enp0s31f6), but not on the bridge device itself (vmbr0). The tap interface for the VM had nowhere to attach to.

The “bridge-vids” Revelation

My /etc/network/interfaces configuration looked like this:

auto vmbr0

iface vmbr0 inet manual

bridge-ports enp0s31f6

bridge-stp off

bridge-fd 0

bridge-vlan-aware yes

bridge-vids 1 50 60I had assumed—like a reasonable person who reads documentation—that `bridge-vids 1 50 60` would add those VLANs to the entire bridge configuration.

Wrong.

bridge-vids only applies VLANs to the bridge ports (the physical interface). It doesn’t touch the bridge device itself. The bridge device needs VLANs added explicitly.

Why does this matter? Because when Proxmox creates a tap interface for a VM with a VLAN tag, it needs to add that tap interface as a member of that VLAN *on the bridge device*. If the bridge device doesn’t have that VLAN, the tap interface can’t join it.

VLAN 1 works automatically because it’s the default PVID on bridge devices. Any other VLAN? You have to add it manually.

The Fix

The solution was adding explicit post-up commands:

auto vmbr0

iface vmbr0 inet manual

bridge-ports enp0s31f6

bridge-stp off

bridge-fd 0

bridge-vlan-aware yes

bridge-vids 1 50 60

post-up bridge vlan add dev vmbr0 vid 50 self

post-up bridge vlan add dev vmbr0 vid 60 selfApplied the changes, stopped the VM, started it again (not restart—stop then start), and suddenly: DHCP lease acquired. VM online. Victory.

Day 2: pxhp and the Networking Service Trap

Armed with my new knowledge, I confidently configured pxhp. Four NICs bonded in LACP, VLAN-aware bridge, proper `post-up` commands. I even remembered to configure the bridge with VLAN 50 support from the start.

Then I made a critical mistake: I ran systemctl restart networking.

All 17 VMs instantly lost network connectivity.

Why Restarting Networking is Evil

When you run systemctl restart networking on a Proxmox host:

- The bridge goes down

- All tap interfaces are removed

- All VMs lose their network connection

- The bridge comes back up

- The tap interfaces… don’t automatically recreate

Your VMs are now running but completely isolated from the network. You have to stop and start each VM to recreate its tap inte4rface.

The Better Approach: Shutdown VMs first, then restart networking. Or just reboot the entire host and let the VMs come back up automatically with proper tap interfaces.

I learned this the hard way when I had to stop and start 17 VMs manually. In the middle of the migration. With production workloads running.

Day 3: Kubernetes and the Blue-Green Migration

With both Proxmox hosts properly configured, it was time to migrate the Kubernetes clusters. I had three:

- Non-production (3 VMs)

- Internal (8 VMs)

- Production (5 VMs)

The problem: Kubernetes nodes can’t easily change IP addresses. The IP is baked into etcd configuration, SSL certificates, and about seventeen other places. Changing IPs means major surgery with significant downtime risk.

The Solution: Blue-green deployment, Kubernetes-style.

- Provision new nodes on VLAN 50

- Join them to the existing cluster (now you have old + new nodes)

- Drain workloads from old nodes to new nodes

- Remove old nodes from the cluster

- Delete old VMs

No IP changes. No etcd reconfiguration. No downtime. Just gradual migration while workloads stay running.

I started with the non-production cluster as a test. The entire migration took maybe 30 minutes, and the cluster never went offline. Workloads migrated seamlessly from old nodes to new nodes.

As of today, I’m 1 cluster down, 2 to go. The non-production cluster has been running happily on VLAN 50 for a few hours with zero issues.

What I Learned

bridge-vidsis a lie. Or rather, it’s not a lie—it just doesn’t do what you think it does. It configures bridge ports, not the bridge device. Always add explicitpost-upcommands for VLAN membership.- Never restart networking on Proxmox with running VMs. Just don’t. Either shutdown VMs first, or reboot the whole host. Future you will thank past you.

- Blue-green migrations work brilliantly for Kubernetes. Provision new nodes, migrate workloads, remove old nodes. No downtime, no drama.

- Stop and start, never restart. When you change VM VLAN configuration, you need to stop the VM then start it. Restart doesn’t recreate the tap interface with new VLAN membership.

- Test on simple hosts first. I started with pmxdell (1 VM) before tackling pxhp (17 VMs). That saved me from debugging VLAN issues with production workloads running.

The Current State

Infrastructure migration progress:

- ✅ Proxmox hosts: Both on VLAN 60 (Management)

- ✅ Kubernetes (non-prod): 3 VMs on VLAN 50

- ✅ Kubernetes (internal): 7 VMs on VLAN 50

- ✅ Kubernetes (production): 5 VMs on VLAN 50

Next steps: Monitor the clusters for 24-48 hours, then migrate internal cluster. Production cluster goes last because I’m not completely reckless.

You’re missing an agent…

The astute among you may notice that my internal cluster went from 8 nodes to 7. As I was cycling nodes, I took the time to check the resources on that cluster, and realized that some unrelated work to consolidate observability tools let me scale down to 4 agents. My clusters have started the year off right by losing a little weight.

—

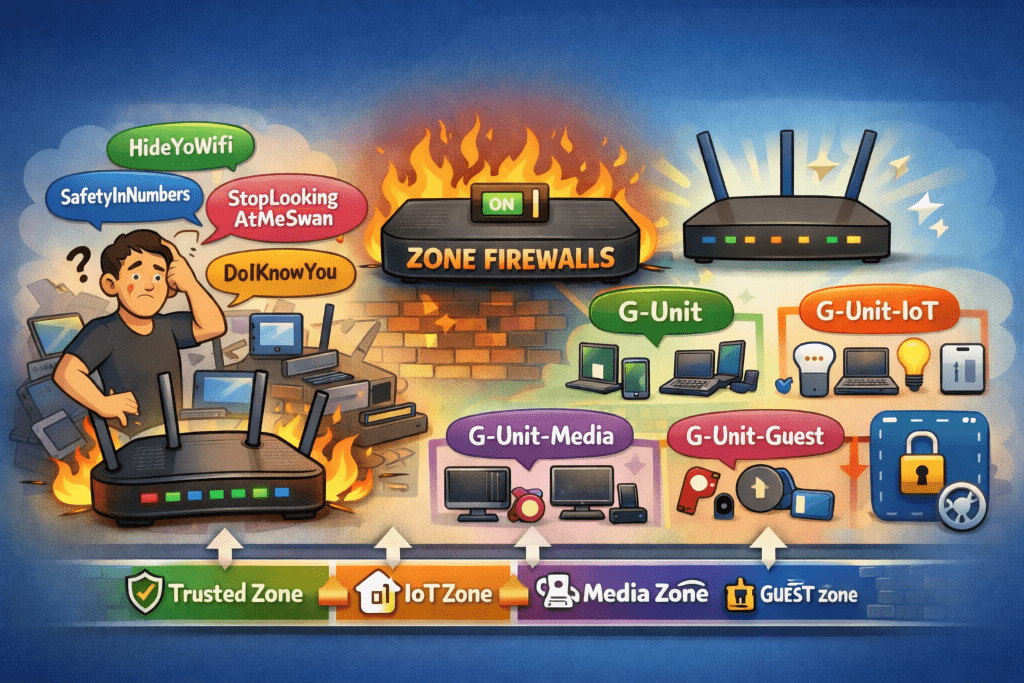

Part 3 of the home network rebuild series. Read Part 2: From “HideYoWifi” to “G-Unit”