After migrating my Proxmox hosts and the first Kubernetes cluster to their proper VLANs, I took a moment to appreciate my newly segmented network. Everything was isolated. Firewall policies were working. Life was good.

Then I looked at my network topology diagram and had a realization: my reverse proxy was in completely the wrong place.

The Current Setup

My reverse proxy (m5proxy, running nginx) handles all external HTTP/HTTPS traffic coming into my network. It’s the front door for everything—from my personal website to various services I self-host.

Its current location:

- Physical location: Connected to ProCurve switch, Port 23

- VLAN membership: VLAN 60 (Services)

- Purpose: Reverse proxy to services on VLAN 50 (K8s) and VLAN 60 (other services)

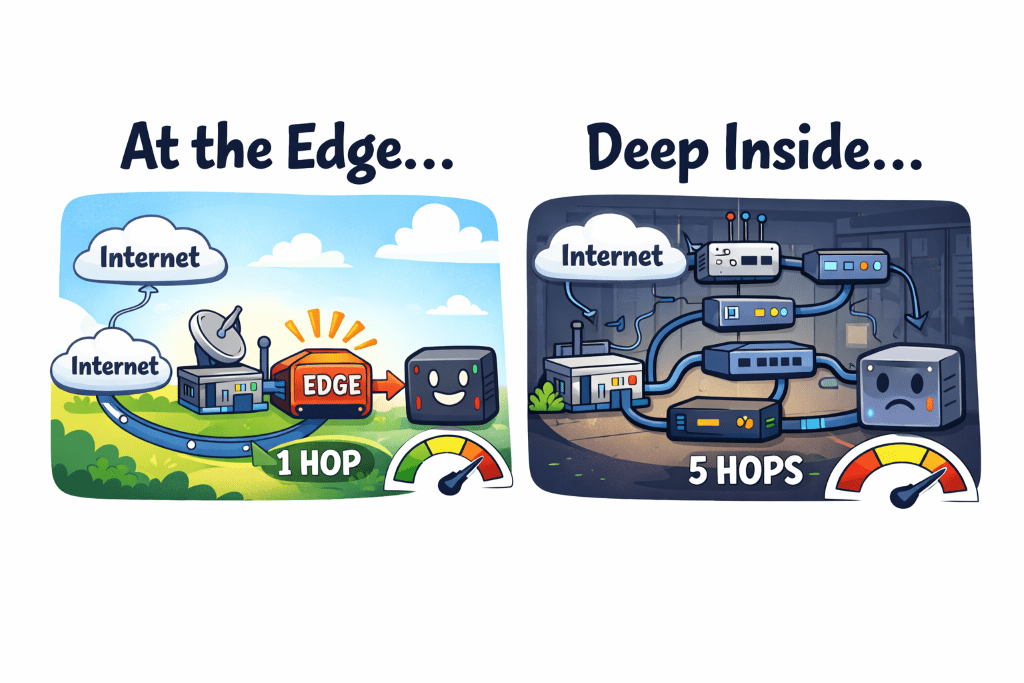

Now, let’s trace the network path for an external request to a Kubernetes service on VLAN 50:

Internet → UCG Max (gateway) → ProCurve switch (Port 23) → m5proxy → ProCurve switch → UCG Max (inter-VLAN routing to VLAN 50) → ProCurve switch (Ports 13-16, bonded to pxhp) → Kubernetes VMCount those hops: 6 total (3 switch hops, 3 routing decisions).

For every. Single. Request.

The Question

Why is my reverse proxy sitting behind the ProCurve switch when it’s handling traffic from the internet?

The UCG Max is my gateway. It’s where external traffic enters my network. So why was I routing that traffic to the ProCurve switch just to hit the reverse proxy, which then routes back through the switch to reach its destination?

Because I’d never questioned it. The ProCurve switch had available ports. The reverse proxy needed a port. Done.

The Better Way

The UCG Max has LAN ports. Physical ethernet ports that I can configure for specific VLANs.

What if I connected m5proxy directly to the UCG Max?

New network path:

Internet → UCG Max (m5proxy directly connected) → ProCurve switch (Ports 13-16) → Kubernetes VMCount those hops: 3 total (1 switch hop, 2 routing decisions).

50% reduction in network hops for every external request.

The Architecture Argument

Beyond the performance improvement, there’s an architectural argument: edge services belong at the network edge.

My reverse proxy is the entry point for all external traffic. It’s literally the edge of my internal network from an external perspective. So why was it sitting behind a switch, requiring traffic to traverse my internal infrastructure just to reach it?

It should be as close to the gateway as possible. Which means: directly connected to the UCG Max.

The Configuration

This turned out to be surprisingly straightforward:

Step 1: Configure a UCG Max LAN port for VLAN 60 (Services)

- Via UniFi Controller → Port Management

- Set port profile to VLAN 60

- Configure as access port (not trunk—m5proxy only needs VLAN 60)

Step 2: Physical cable move

- Unplug ethernet cable from ProCurve Port 23

- Plug into configured UCG Max port

- Wait for link to come up (~10 seconds)

Step 3: Verify connectivity

- SSH to m5proxy:

ssh root@m5proxy - Test gateway:

ping 192.168.60.1(UCG Max) - Test cross-VLAN:

ping 192.168.50.x(K8s nodes) - Test external:

ping 8.8.8.8

Step 4: Test reverse proxy functionality

- From external network:

curl -I https://mattgerega.com - Verify proxied requests work correctly

- Check nginx logs for successful forwards

Total downtime: Maybe 2-3 minutes while the cable was being moved.

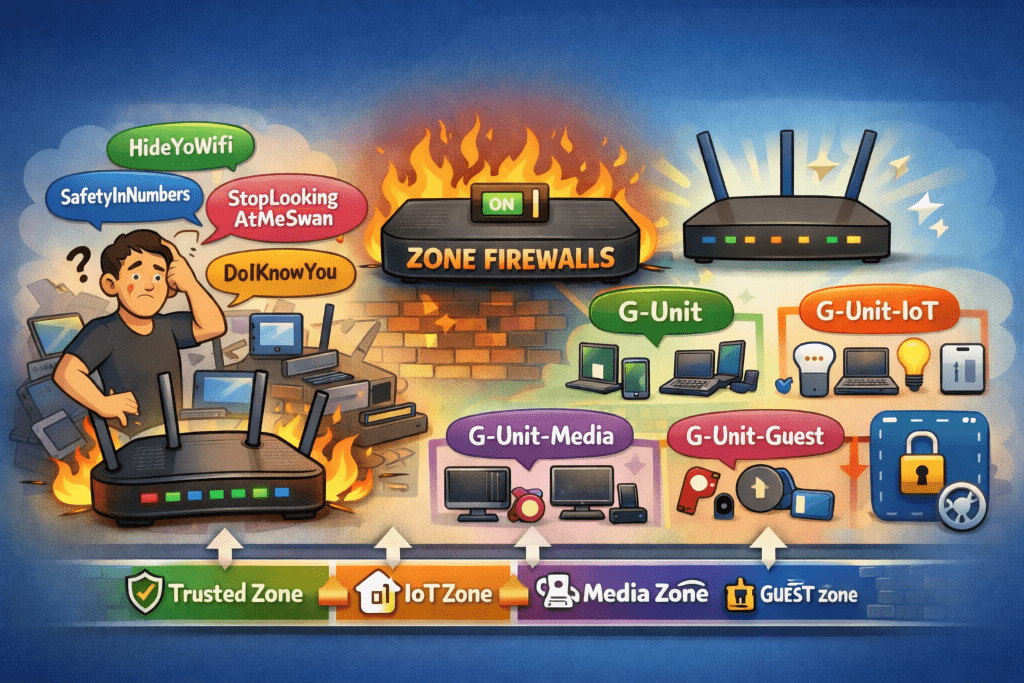

The Firewall Consideration

One thing to verify: m5proxy on VLAN 60 needs to be able to forward requests to services on VLAN 50 (K8s). That requires a firewall rule:

Services (VLAN 60) → Lab (VLAN 50): Allow

This rule should already exist if you’ve properly configured zone-based firewalls. But it’s worth double-checking before you move the proxy, because if that rule is missing, your external traffic will hit the proxy and then… nowhere.

Quick test from m5proxy before the move:

# Can the proxy reach K8s services?

curl -I http://192.168.50.x:portIf that works, the firewall rules are correct.

The Results

After the move:

- External requests are noticeably snappier (hard to measure precisely, but the difference is perceivable)

- Network topology is cleaner—edge service at the network edge

- ProCurve Port 23 is now free for other devices

- Traffic patterns make more logical sense

And the best part: everything still works. No broken services. No mysterious connectivity issues. Just cleaner architecture and better performance.

When NOT to Do This

Fair question: why doesn’t everyone do this?

Reason 1: If your reverse proxy needs to be on multiple VLANs, you’d need a trunk port on the UCG Max. That’s more complex than a simple access port configuration.

Reason 2: If your reverse proxy is a VM instead of a physical device, it makes sense for it to live wherever your hypervisor is. Don’t complicate your VM networking just to save a hop.

Reason 3: If your gateway has limited ports and they’re all in use, you don’t have a choice.

In my case: m5proxy is a physical device, it only needs VLAN 60 membership (forwarding to other VLANs happens via routing), and the UCG Max had available ports. Perfect use case.

What I Learned

- Question your topology. Just because something works doesn’t mean it’s optimal. I’d been routing traffic through unnecessary hops for no good reason.

- Edge services belong at the edge. If something handles external traffic, put it as close to your gateway as possible.

- Port availability matters. Having available ports on your gateway opens up architectural options you might not have considered.

- Testing is cheap, fixing is expensive. Spend 5 minutes verifying firewall rules and connectivity before you move cables, not after.

- Physical changes are faster than you think. I spent more time planning this move than executing it. The actual cable swap took maybe 60 seconds.

—

Part 4 of the home network rebuild series. Read Part 3: Proxmox, VLANs, and the Bridge That Wasn’t